Larry Summers’ Chart is Fine

There are no hard rules behind data analysis

Larry Summers recently created a plot comparing our current inflationary period to the late 1970s, with the intent of warning us of the ongoing risks of inflation. The way he created this plot upset many people. Some data viz types focused on the double axes, some on how he overlaid the data from the past. Others thought he lacked an economic basis to compare it to the 1970s, or that his comparison somehow violated rules of statistical rigor.

While the reason people disliked his plot varied, it seemed like everyone was concerned that Summers broke some rule of how good economic analysis ought to be performed. As though there are clear rules you have to follow to do things correctly, and if you follow these rules you are blessed with validity, whereas if you break the rules your analysis is flawed.

The problem is that there are no rules written in stone, and understanding this is the difference between having a surface level understanding of how inference from data works, and reasoning from the primitives of the field.

Summers wrote the same thing in each of his two tweets, saying that he finds the analogue to past inflation events to be ‘sobering.’ A lot of the criticism of his posts comes from the exact semantics of what he wrote, so let’s just go ahead and note that the definition of ‘sobering’ is “creating a more serious, sensible, or solemn mood.” He did not say “this overlay is predicting the future now.” He said that being aware that we are following the same path is “sobering.”

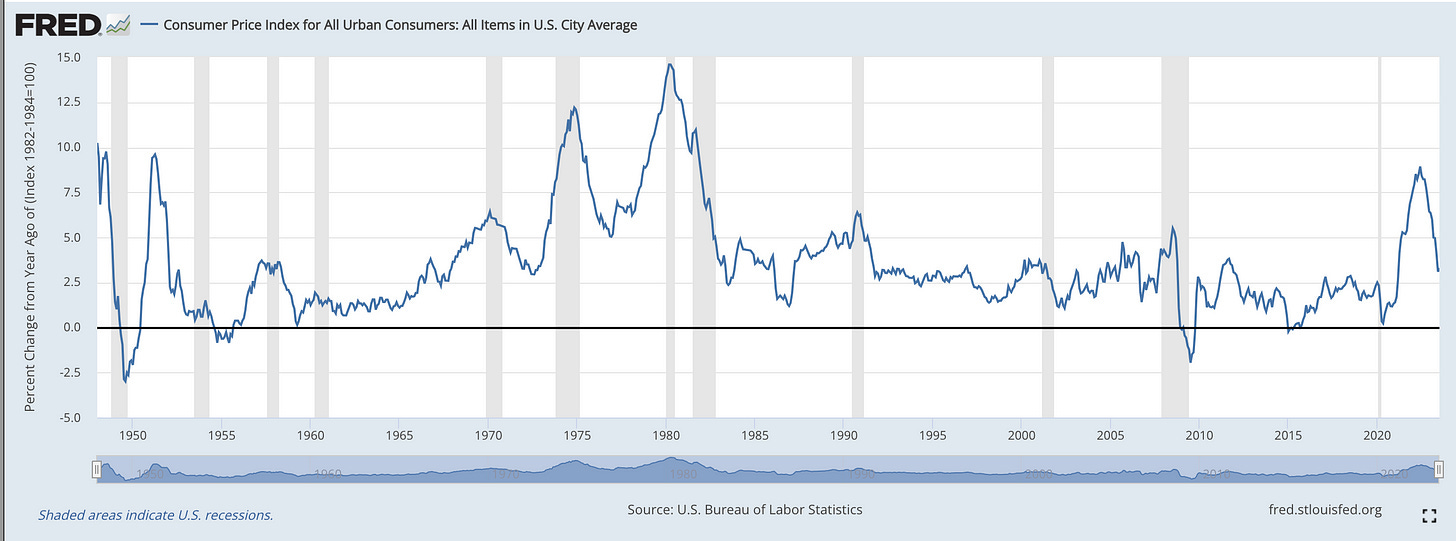

The plot itself simply shows a current path of inflation, overlayed on top of the 1970s inflation era of the US, particularly the lowering of inflation in the mid 70s that was then followed by a resurgence in 1979.

Why People Didn’t Like it

I read a lot of tweets that disliked Summers’ post, both as quote tweets to the original, and as replies to my own tweet. These are the major categories I classified them into.

Norms of discussion

One underlying issue of many gripes with Summers’ plot is that they think he is saying something in addition to what he actually said. Some believe he’s saying the situation today is exactly the same as the 1970s, or that the overlayed path from 1979 is in fact his point forecast prediction for the coming five years. If this was the case I would agree with all the criticisms. The only problem is he didn’t say any of these things. He only remarked that it’s sobering that in the past we thought we controlled inflation, only to have it come roaring back.

I think the reasoning most people employ here is something like: “I’ve seen lots of cases where people align charts on the time-axes incorrectly and use that to imply that what happened in the past will happen again. These people are wrong, and Summers’ plot looks the same as theirs. So this must be what he thinks and he is also wrong.” What people are doing here is predicting what Summers believes beyond exactly what he wrote. In addition to being impolite, this is an inefficient way to communicate.

So long as someone is, in general, a person who operates in good faith, instead of trying to read their mind as to what they’re actually trying to say, you should either ask them to clarify, or in the absence of clarifications not make assumptions as to what they’re really saying.

Differing Axes

The biggest complaint was from people who were very upset that the two Y axes were different in the first plot, since it overlays both time-series on top of each other. While I do think the second plot is better, it’s not that big of a deal even in the first plot. A lot of people look for shifted axes as some sort of ‘tell’ for a bad plot, as it’s a common tactic used by deceiving chartists. In that sense it can sometimes represent a type of over-fitting. Is that really the case here, though?

While it’s true that inflation was higher in the 70’s than the comparison today, both are cases of inflation regimes where the central bank lost control. Having lost control, only for the Federal Reserve to have to fight to regain it, is the key concept we’re looking to match against here. The fact that inflation peaked at 7.5% now vs. 15% in the 70s isn’t challenging the central inference that Larry Summers is making. The point he is making is you can think you’ve controlled inflation, when you actually haven’t. So having two different vertical axes is fine, in that it supports the inference he’s making.

In this plot you can see that other than the recent inflation spike, the 70s and 80s were the only other serious period of modern inflation.

In addition to the Y axis, it really upset people that the X axis was shifted. It’s true that this sort of chart abuse happens with stock market grifters looking for the next head-and-shoulders pattern, or who overlay the stock market with some previous cherry-picked stock market crash. In that world, there are so many dips and crashes that you have an issue with a garden of forking paths. You can always find some pattern in the past 50 years in the stock market that aligns with yours today.

If Summers was making charts like this about equity markets I would agree with you. He’s not though - he’s making charts about inflation. There has been one major prior inflation regime, and that was in the 70s. He’s just saying “this is what it looked like last time this thing happened.” A lot of people have it so ingrained in them that shifting or rescaling axes is something that people operating in bad faith do, that they seem to have forgotten there is nothing actually wrong with it if it’s warranted.

Lastly, if the two axes are different, just look at them separately. Why is this so hard? Are you easily misled if two axes are different? There is nothing inherently right or wrong about having multiple axes. In some sense that’s exactly what calculating the correlation coefficient does: looking for how data varies together irrespective of the scale.

There isn’t a theoretical basis to compare to the 70s.

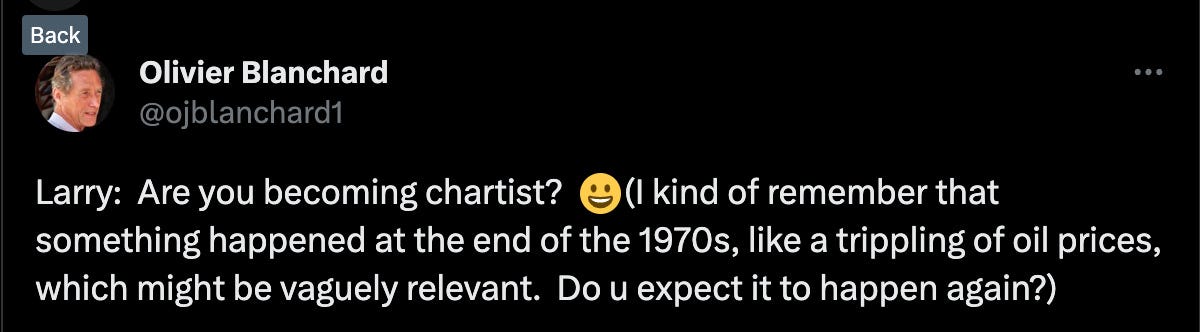

Olivier Blanchard made the following tweet (although apparently in good fun, as he followed it up by saying he agreed with Summers’ most recent article on inflation risks).

Blanchard is a smart economist, but he’s also following a rule when comparing our current period to the past. It’s true that an oil shock caused the resurgence of inflation in 1979. It’s not true that a comparison to the past is only justified if you think the proximal cause of the past event will happen again. It’s also not true that you need some sort of theoretical justification for a forecast.

The oil shock of 1970 happened during a weak point for our monetary system. The reasoning here is that the recent period of inflation put our economic system into a weaker than normal state. This could be due to public fears of follow-on inflation, resulting in the expectation that inflation would return. People might think the type of central bank that resulted in inflation the first time would be the type that could cause it to happen again — and since economics works by expectation, that belief itself could cause inflation.

Attributing the 1979 inflation spike just to oil, rather than to an interaction effect between oil and a weakened monetary state due to inflation itself, is not justified by the data. The counterfactual we wish we could know here is what the oil shock of 1979 would have done to inflation had it occurred during a period of a well-functioning economic environment with no recent inflationary period.

If we look around today, people seem to be uneasy. The consumer sentiment polls are very negative. By the traditional numbers the economy is doing fantastic, yet if you say the economy is doing well, everybody gets mad at you. Is it that crazy of a hypothesis that, given consumer fears, we may not have the slack to deal with a new shock? It probably wouldn’t be oil again, it would be whatever other thing we aren’t expecting. If that happens people may freak out that inflation is going to return, dramatically increasing the chance that it actually does.

In fact, this was one of the mistakes initially made by the transitory inflation camp. While it’s not clear exactly how the attribution shakes out, they didn’t consider the war in Ukraine or other ongoing supply chain issues during their initial forecasts. While a follow-on shock may not be the most likely event, when making predictions it’s probably a good idea to be prepared for another shock to an already weak system. You might even call the concern for such a thing sobering.

More generally, macro-economic theory isn’t exactly a field with a killer predictive record. In fact, there was a large divergence in the 1970s when it was discovered that modern time-series methods were beating the large structural macro-economic models. The most successful class of models that we used when I worked at the Federal Reserve were the ones that used a purely time-series approach towards creating forecasts, with very few structural or macro-economic oriented restrictions.

You can certainly sound smart by bringing up a lot of very complex economic theories, tying them to the current narratives and events going on, and using that as the basis for your prediction. It’s a shame that this is barely helpful in out-of-sample accuracy.

Part of the reason extrapolation algorithms also work so well is that the process in the historical time-series itself captures a lot more information than you might think. While we might be tempted to explain 1979 inflation as a special case due to oil, doesn’t it seem likely that periods of monetary errors that cause inflation, which themselves are made due to tricky situations, are likely to be correlated with other events that cause shocks to an economic system?

How do you estimate the distribution of future inflation?

There is an underlying rule that people want to follow, which is that by comparing the risk today to the outcome in 1979 in a plot, we haven’t built a ‘proper statistical model’. I disagree with this point, and for the purposes of the inference Summers is trying to make, I would even argue that this plot is potentially a better model than a more complex econometric forecast for this inference.

In the world of macro-economic forecasting, point forecasts (forecasts of the expected value) are nearly impossible to get right. Not only that, but for a time-series like inflation they are effectively always mean-reverting.

The class of time-series models that are fit to inflation tend to revert to the mean. The reason is that in the historical data, on average, huge terrible things don’t happen, so on average you shouldn’t predict that they happen. The reason that’s in the historical data, is that the Federal Reserve has an inflation target, so they are steering the ship to always revert back to their expected inflation target.

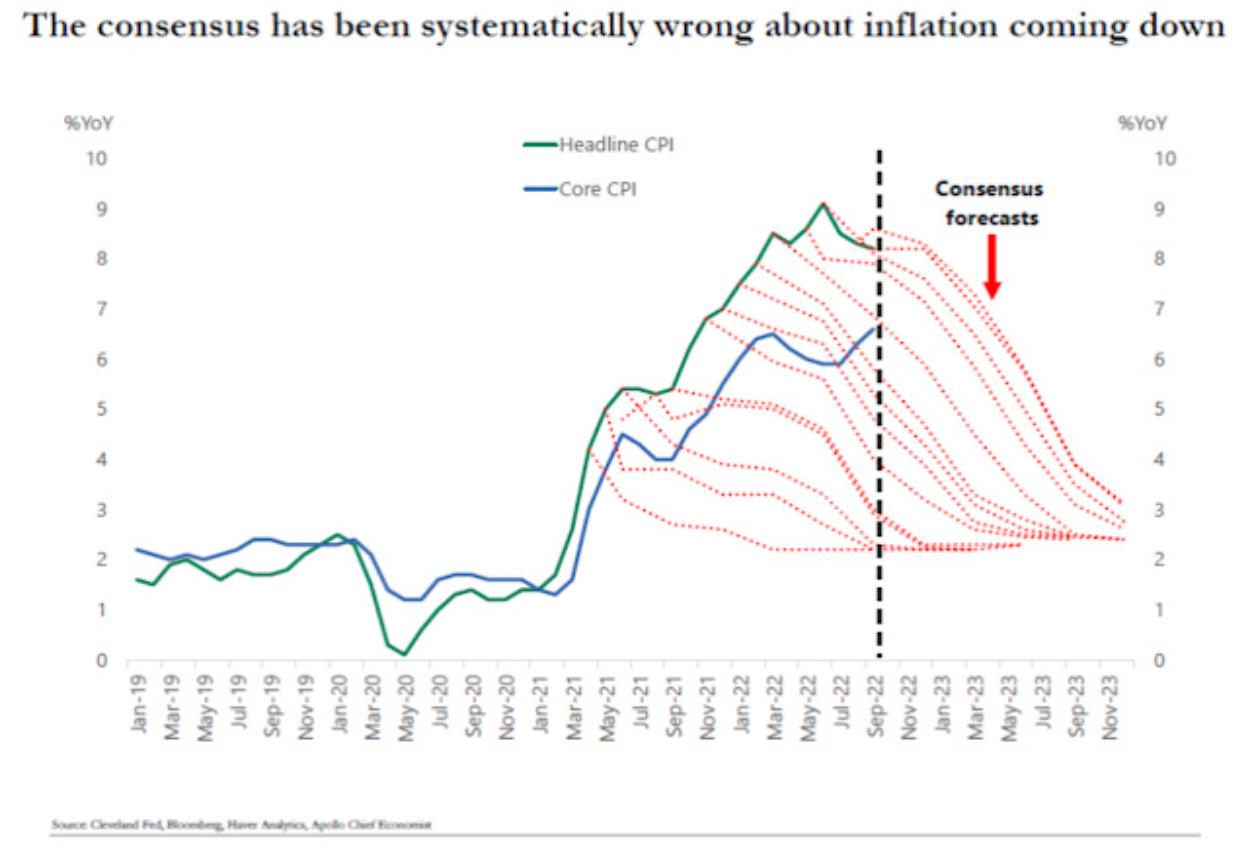

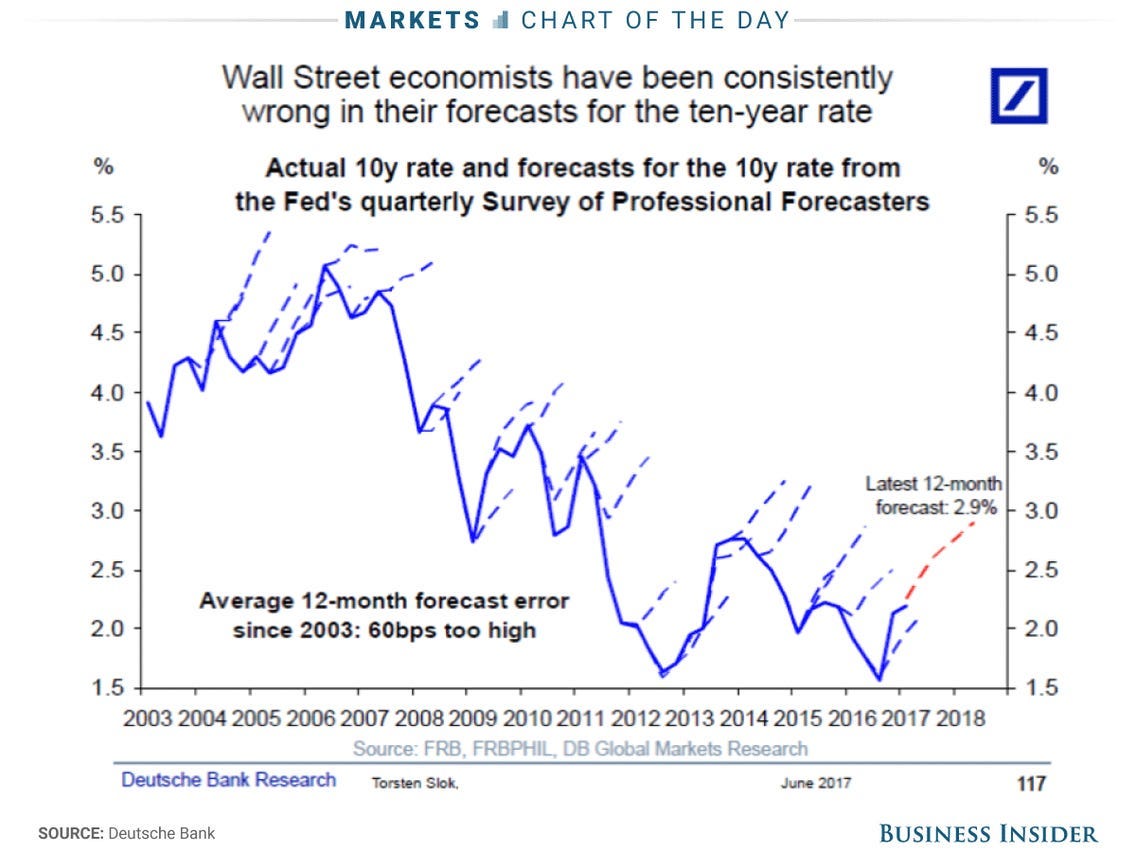

These are my two favorite plots, where the dotted lines were averages from professional finance forecasters for recent CPI, and the 10-year treasury rate from 2003-2018, respectively. The take-away from these isn’t that forecasters are stupid; it’s that forecasting is so hard it’s embarrassing.

When looking at the time-series alone, there are two general approaches to build a distributional forecast. One, you specify a function, e.g. a normal distribution or a fat-tailed distribution, and fit that to your data (usually in a time-series model) and then sample from it. Alternatively, you can choose to not use a function, and simply use the empirical distribution. In a world of asymptotic data, you should just use the empirical distribution, which would converge to the true distribution.

Of course, when you only have an effective sample size of a few data points, due to the rare occurrence of major inflationary events in the US, you are in a difficult situation trying to create a prediction interval. If you fit a distribution, the tail of your distribution will be supported by only a handful of data points. If you use the empirical distribution, you would effectively do exactly what Larry Summers did in his plot.

You would try to align where we are today with past inflationary events and look at what happened next. Summers didn’t assign a probability to his event, but for his inference it wasn’t necessary. All he had to do was show that this bad event had happened before to people who prematurely celebrated victory over inflation.

It’s important to remember that there is nothing special or magical that happens when you fit a model to data. In all cases, you’re using some sort of functional structure to compress your data. If there have been only a few past inflation events in the US, you are fundamentally constrained on information, so there isn’t much to compress. In those cases your structural assumptions end up being more load-bearing than your data. In these cases you may never do better than just looking at the past inflation events and comparing them to today.

Evaluating Analysis on Its Own Merits: The Fallacy of Pattern-Matching in Data Interpretation

The common thread underlying most of these claims, and most of the people doing them, is that they are pattern-matching any type of analysis to other forms of analysis, and determining if it’s good or bad on those merits. This chart looks like another chart done by a stock grifter. Or this choice of axes looks like what deceptive people do. Or Summers probably was implying something different than what he wrote. Or Summers didn’t do the theory song-and-dance to justify his claim.

In all these cases, the criticism is not addressing the exact statement and piece of evidence, but is instead trying to make an inference based on the validity of other forms of analysis that match Summers on some features of his analysis.

The most fundamental lesson I’ve learned both in mathematical statistics is that there is no moment where statistics takes on any form of deep validity. Nothing magical happens when you estimate a model as opposed to plotting some data next to some older data.

If anything, there is a deeper beauty to these wildly simple forms of analysis. In return for their relative simplicity, you get a robustness to misspecification and overthinking a problem that is the root of so many issues in modern data science.

The reality is that if Summers had made some slightly more wonkish post, where he included the distribution of inflation based off of some Bayesian vector auto-regression model he fit to the data, no one would have cared to dunk on him. It also wouldn’t have been meaningfully different from what he did, because the tails of those distributions would be determined almost entirely by the exact same few data points you see in that plot.

Some of the first models I coded were basic auto-regressive models or regressions. I remember feeling as though they were telling me something deep about the world, hidden to everyone else. Over time as I kept learning more about the lower level statistical machinery, I was both astounded by the mathematical beauty of the field, of which I’ve barely scratched the surface, and simultaneously realizing there was nothing magical happening at any point of the model fitting process.

We might be tempted to think that with recent breakthroughs in AI, and training on massive amounts of unstructured data, this is becoming less true. In that sense it’s deceptive, because even as the permissible data sources increase to all text and media, we will still remain information constrained on questions where we are trying to infer the future of complex systems with limited training data. All the unstructured text in the world won’t make up for the fact that we’ve observed a high inflation environment only a few times in US history.

It’s sobering to think that sometimes the best you can do is plot two lines, one from a previous era, and say “oh man, what if this happens again?”

she larry on my summers til i inflation